In 2012, I made a journey to Paris and Sarajevo in search of Bolero. Ravel wrote the music in Paris in 1928, and Torvill and Dean danced to it in Sarajevo in 1984. In 2014, I will premiere a performance that marks the 30th anniversary of the Winter Olympics and the centenary of the First World War. Ravel fought in the First World War and was lost in the woods outside Verdun for 10 days. Eight years after the Olympics, the Zetra Stadium where Torvill and Dean won gold was bombed during the Bosnian War. The story I am now telling travels between Paris and Sarajevo, and begins and ends with these two wars.

I have been listening to Bolero for two years now and when you play it so much you hear it even when it isn’t there. In the sound of footsteps. In the ring of a mobile phone. In the beep of traffic lights. In the rhythm of trains. Ravel is buried in Levallois-Perret outside Paris, and when you visit his grave you hear the sound of trains pulling into Paris braking to the rhythm of Bolero. The mountains around Sarajevo turned the city into a speaker during the siege; the sound of gunfire reverberated so there was never silence.

Bolero was written for a ballet, as a composition to be danced to and not listened to alone. Ravel said "It has no music in it" and was surprised by the critical acclaim it received. It was one of the last pieces of music he wrote. Torvill and Dean invited a composer to edit the 17-minute original to fit the Olympic time limit of four minutes 10 seconds, but they were told that the minimum time to which it could be condensed was four minutes 28 seconds. However, if their skates did not touch the ice for the first 18 seconds then it would be acceptable, so Bolero started with them kneeling on the ice for those 18 seconds.

Ravel urged conductors of Bolero not to go too fast as it built to its crescendo. He urged them to "stick to the tempo". That is what we are trying to do with the performance, to let the music tell our story and its rhythm reveal itself in other ways. In the sound of footsteps. In the tap of a baton on a music stand. In the way water falls. In the way a man whistles as he sweeps the stage. I watched Torvill and Dean dance with the Olympic torch when it passed through Nottingham last year. Before they danced the ice was cleaned and Bolero was played on the big screen in silence. The audience hummed the music. When I visited the Zetra Stadium there was so much snow on the roof it was dripping through the ceiling into buckets on the floor. In our show, we arrange five buckets into the shape of the Olympic rings and find Bolero in the drips.

I imagine Ravel listening to gunfire lost in the woods outside Verdun in 1914. The rat-a-tat-tat of warfare informed the music he would later write. If you listen to the side drum in the background of Bolero it sounds like gunfire. Ravel was fighting in a war triggered by an assassination in Sarajevo. Archduke Franz Ferdinand was shot by a Serbian student, Gavrilo Princip. There were three shots, enough to kill the Archduke and his wife, Sophie. Archduke Franz Ferdinand lived in the Palace of Belvedere in Vienna. Ravel composed Bolero on a piano in his house outside Paris, also called Belvedere.

. He also composed a piano sonata for a one-handed pianist. Princip died of Tuberculosis in a prison in Terezin. His arm was withered to such an extent it was tied up with piano wire before it was amputated. It was the arm that had held the gun that fired the bullet that started the First World War in Sarajevo.

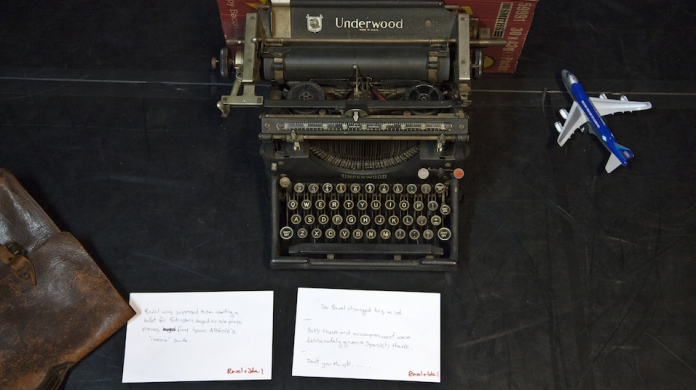

We shared a work-in-progress of Bolero in April 2013. Three artists from Sarajevo, two artists from Nottingham and one artist from Berlin spent a week weaving these ideas together. It is a complex raveling and unraveling of different strands that relate to the music and my journey to find it. Just as Ravel wrote for different instruments so we have scored our story for different voices, different places and different times. This is a story that takes place to the music. This is a story that aims to stick to the tempo. I have written to Bolero in Ravel’s house and at his graveside, at L’Opera in Paris where it premiered as a ballet, and at the Zetra Stadium where Torvill and Dean danced before bombs fell and seats were turned into coffins. I wrote this to Bolero too.

Michael Pinchbeck is a writer and theatre maker based in Nottingham, UK. Bolero has been supported by the British Council, Arts Council England, Nottingham Playhouse and Making Tracks, a Theatre Writing Partnership project. For more information please go to www.michaelpinchbeck.co.uk or www.makingbolero.wordpress.com.