Dancer and choreographer Jayachandran Palazhy has watched India's contemporary dance scene grow and begin to flourish. He tells Eleanor Turney about pretending to study computer science, reinventing the wheel and not understanding Merce Cunningham

"I was constantly looking for something new"

I was interested in dance from childhood onwards, but never had the opportunity to learn dance properly until I went to university. I remember, as a child, I used to stand in front of a mirror and try and imitate the dances I saw at festivals and things like that. When I went to university, I saved up money and then joined a dance class. Because I was away from home, staying in a university hostel, I had the chance to do that.

After that, I went into full-time dance study, under the pretext of studying computer science, because otherwise my family probably would not have agreed. I moved to Chennai to dance full-time, and it was really intense – we started classes at 6am and then there was studying, teaching classes for children in the afternoon and rehearsals in the evening. It was really a very hard day!

This was primarily classical forms, and we used to learn some folk dance and things, too. I was fascinated and attracted by the classical dance language, but the content of the form really bothered me because it was still talking about religious texts or really old-fashioned notions of man-woman relationships.

I wanted to find a new idiom that would express my own thoughts, experiences and memories. I was constantly looking for something new. But these explorations really helped me to get in touch with what was being attempted in India at that time. I always felt that I was maybe reinventing the wheel, making work that was being made elsewhere. I remember seeing a Merce Cunningham performance in Chennai and asking lots of questions. Some students from American were there and I asked them about it – I was so fascinated by this dance but I don't think I fully understood what he was trying to say. I asked them to tell me, and they said they didn't know either. I realised that maybe I had to find out myself.

"I wanted to find a new idiom that would express my own thoughts, experiences and memories. I was constantly looking for something new."

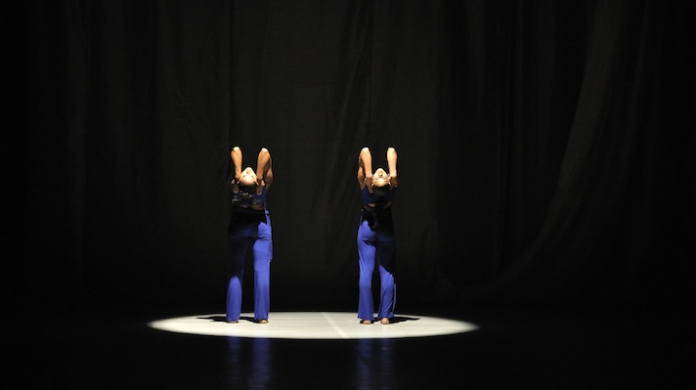

That took me to London, where I joined the London Contemporary Dance School and started my own work. Since then, I've worked in many countries, including the UK, and then back in Bangalore I set up the Attakkalari Centre for Movement Arts. Since 2001, it has really changed the face of contemporary dance in India. We have a few interlinked activities: we have a repertory company that performs all over the world, which has between 10 and 16 paid dancers. We also have the only comprehensive diploma training in the country, for young aspiring dance artists. We have education outreach programmes, taking dance to schools, colleges and into the community, we run all sorts of classes in the evenings and at weekends. We also do research into Indian performing arts and physical traditions. We run a biennial festival, which is the biggest dance festival in South Asia.

"There is a responsibility on artists who are creating work to subject themselves to higher demands of quality, to be much more rigorous."

I think that Indian dance and music have deep roots because they are linked with religion. That means they have benefitted from religious belief but they are also limited by what is permissible. In the beginning of contemporary work, a lot of people were trying to make work but they didn't have any specific techniques or skills or modes of creating work. So they were primarily interested in attempting new ideas, contemporary ideas, but their language, structure and approach remained classical and traditional, because they didn't have the physical techniques or choreographic knowledge or stage technologies.

As a result, a lot of work remained, in my opinion, quite basic in terms of its craft and approach. That is changing now. More and more people are gaining skills and young people are travelling more. Now the problem is that people are attempting anything and everything without making a careful choice about what will help their work. That's where an organisation like Attakkalari can help; we have a training process, we support young choreographers. Now, the country needs some kind of quality control, some evaluation of what goes on in contemporary dance. My sense is that contemporary dance is a training ground. There is a responsibility on artists who are creating work to subject themselves to higher demands of quality, to be much more rigorous.

The thing I would say is that agencies like the British Council can play a role in developing networks, not only in production but also in dissemination of new work. It's one thing to support young choreographers but you ned to also build audiences. The British Council team in India have been particularly active in that.

Jayachandran Palazhy is a dancer and choreographer, and set up the Attakkalari Centre for Movement Arts in Bangalore. He attended British Dance Edition in Edinburgh in February. He was speaking to Eleanor Turney.