Directing The Winter's Tale in Urdu has made Gregory Thompson re-evaluate how he directs, how he uses language and how he thinks about theatre

The world wants Shakespeare

The project initially came about at NAPA, the National Academy of Performing Arts in Karachi. They’ve done various things with the British Council before, including work with Punchdrunk and the Arcola Theatre, who made a piece about the NAPA organisation and the NAPA buildings. They made some innovative work, but I think what they also want here is Shakespeare, so they asked for a British director to come over and do that.

I went out to South Sudan for a week-long workshop a couple of years ago when they were doing a show for the Globe [as part of 2012's Globe to Globe project], and we looked at how Shakespeare works, from the different themes in Shakespeare, to how the language works, how the story works, how staging works and what the Globe looks like. I also toured a production of The Tempest for the British Council ten years or so ago, which went to all sorts of places. The British Council want to show how innovative and interesting British theatre is, and the rest of the world wants Shakespeare, so I’m aware of trying to tick both of those boxes. Another brief for the project was to do a kind of directing class, where actors can learn more about their acting. We use lots of different techniques in rehearsal; we’ve done actioning, we’ve done game-playing, we’ve done physicalising, all kinds of different techniques, so the actors get a taste of the different things we can do.

"The British Council want to show how innovative and interesting British theatre is, and the rest of the world wants Shakespeare..."

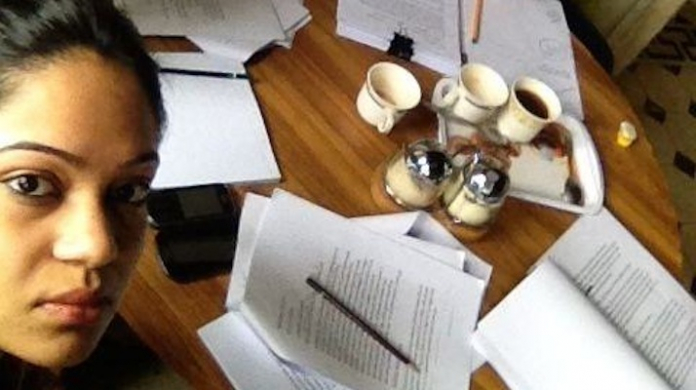

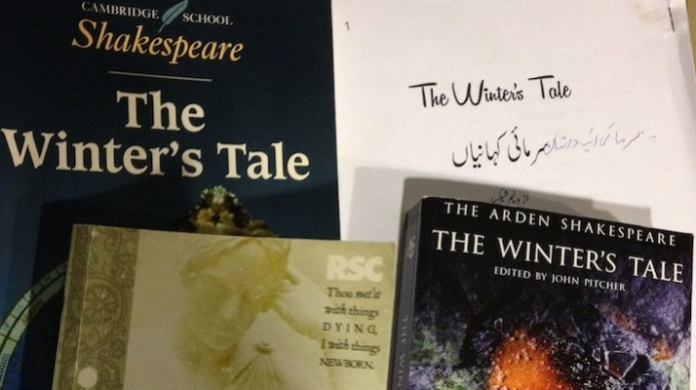

The translation we’ve been working with is based on a 50-year-old translation in classical Urdu, which is highly poetic. We’ve set the second half of the play in 2014, so we needed to modernise the Urdu during the process. Our Winter’s Tale starts in the Moghul era, in 1614, when Shakespeare wrote the play. Then when the play moves forward 16 years to Bohemia in Act Three, we’re actually transposing 400 years to modern-day Pakistan, so we’re using the shifting time frame as part of our geographical shift. The translation has also misunderstood what Shakespeare is saying in some quite crucial places, so again we’ve had to retranslate, but we’ve just managed to finish it today.

What we’ve been doing when looking at the language is actually the same thing that you’d do in England, which is asking questions like “who is this person speaking to?”; “what do they want?”; “what are they saying?”; “how are they saying it?”. We’re asking the same questions in the translation process that we would ask in the production process. Of course we’re losing some of the beauty of Shakespeare’s use of English, but what remains is the ‘how’, or the ideas of the story, and the step-by-step arguments of the speeches.There are some really interesting transitions – for example, Leontes says that Mamillius has “welkin eyes”: that is, blue eyes like the sky. Of course, basically no-one in Pakistan has blue eyes. So if the literal translation doesn’t work, you have to have a translation of the idea.

"We are so lucky in Britain in that not only do we see fantastic theatre that is made there, but we see amazing theatre from around the world."

The difference between working here at NAPA and working in UK drama schools is that here there are people who have heard of Peter Brook and Complicité, and have read books about them, but never had the chance to see a show. We are so lucky in Britain in that not only do we see fantastic theatre that is made there, but we see amazing theatre from around the world. It’s easy to forget that in every rehearsal room you walk into in Britain there are people who have made lots of different shows in lots of different styles with lots of different people, and you can have some amazing conversations, whereas here the theatre community is very small, and they’ve mostly been trained by the same people. So having an outsider come in with different ideas and experiences is quite novel.

What’s been most interesting about working here is that when I came to audition and workshop with the actors and with some of the final year students from NAPA, I found that they were so hungry for the very best of what theatre is, and that really puts you back in touch with your idealism. You go away and get reconnected to your own theatre values, whereas of course in the UK there’s a whole series of distractions, from earning a living, to making a show that sells, to getting the next job, and you forget to ask “what do I think theatre is really for?”.

Credits

Gregory Thompson was talking to Eleanor Turney. Follow Gregory on Twitter for updates from Pakistan, and follow @UKTheatreDance for all the latest news, blogs and opportunities from the Theatre and Dance team.